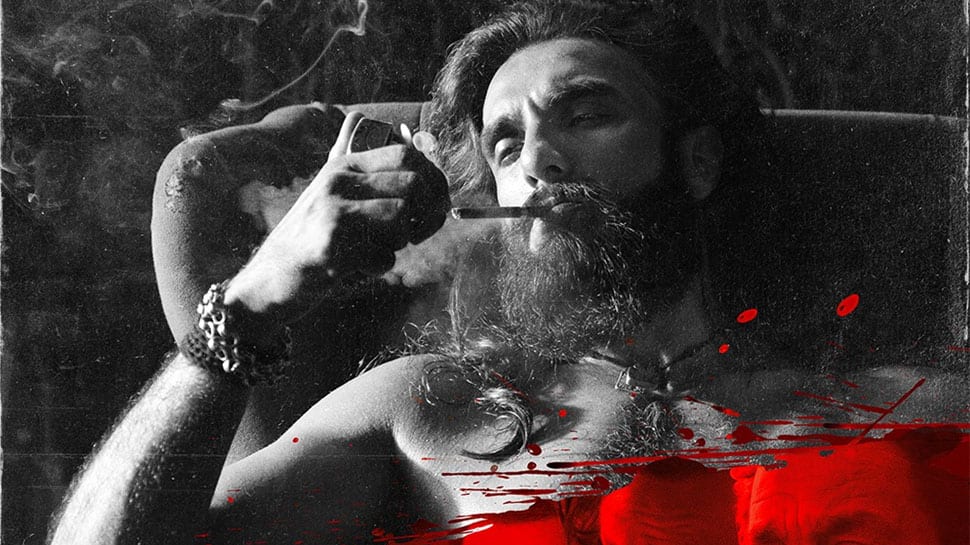

Haq Review: As Bollywood movie ‘Haq’ hits theatres today, Yami Gautam plays the role of a woman who changed the idea of justice in India. Her name was Shah Bano Begum, a 62-year-old mother of five who lived in Madhya Pradesh’s Indore. In 1978, her life took a turn that soon became a storm across the country. What began as her fight for dignity turned into one of India’s most talked-about court cases. It reached the Supreme Court, echoed in Parliament and even touched the story of the Babri Masjid.

The film, which also stars Emraan Hashmi, draws inspiration from that 1985 Supreme Court judgment. Before its release, it has already found itself in a new courtroom drama. The daughter of Shah Bano has filed a case, alleging that the filmmakers used her mother’s story without consent.

A Fight That Began At Home

In 1978, Bano’s husband, advocate Mohammed Ahmad Khan, ended their 43-year marriage by pronouncing “talaq” thrice in one go. He sent her a small monthly allowance for a few months and then stopped it. Left without means to survive, she took her fight to court.

She sought maintenance under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), a law that required a person to support their spouse or dependents if they had the means to do so. It also extended this right to divorced women who had not remarried.

But her husband contested it. He argued that, under Muslim Personal Law, his duty ended after the “iddat” period (roughly three months after divorce), during which he said he had already provided for her. He claimed that by paying her “mehar” (the dower promised at marriage) and supporting her during that period, he had fulfilled all obligations.

A local court ordered him to pay her Rs 25 a month. The Madhya Pradesh High Court raised it to Rs 179.20. Khan appealed against the High Court order in the Supreme Court.

A Verdict That Changed India

On April 23, 1985, a five-judge Constitution Bench led by then Chief Justice YV Chandrachud dismissed Khan’s appeal and stood by the High Court’s order.

The verdict said that Section 125 was a secular law and applied to every Indian citizen, regardless of religion. The judges said the intent of the law was to prevent destitution and protect the dignity of women.

A divorced Muslim woman, therefore, was entitled to maintenance even after the “iddat” period if she could not support herself.

The court also referred to verses from the Quran, interpreting them to mean that Islam itself placed an obligation on a husband to care for his divorced wife. The judges said that the promise of a Uniform Civil Code (UCC), mentioned in Article 44 of the Constitution, remained unfulfilled.

The Storm That Followed

The verdict set off waves across the country. Sections of the Muslim community, led by the All India Muslim Personal Law Board, called the ruling an intrusion into religious law. Protests were held, accusing the government of undermining Muslim identity.

Under pressure, the then Rajiv Gandhi government, which held a massive majority in Parliament, passed The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986. It effectively overturned the apex court’s decision.

The new law stated that a divorced Muslim woman could receive “reasonable and fair provision and maintenance” only during her “iddat” period. After that, her upkeep would be the responsibility of her relatives or, failing that, the state waqf board.

That year saw another turning point. In Uttar Pradesh, the gates of the Babri Masjid were opened. Both moments altered India’s politicial discourse – one over rights and religion and the other over faith and power.

The Law Challenged Again

Soon after, the constitutional validity of the 1986 law was challenged by Danial Latifi, the lawyer who had represented Bano. The case reached the Supreme Court again in 2001.

A five-judge bench upheld the 1986 Act but gave it a broader interpretation. The judges ruled that while the husband had to pay within the “iddat” period, the amount must be large enough to provide for his ex-wife’s lifetime unless she remarried.

This preserved the essence of the Shah Bano judgment that a woman’s dignity must not depend on the calendar.

Decades Later, A Final Word

The debate did not end there. Confusion remained: could a divorced Muslim woman still approach the court under Section 125 of the CrPC or was the 1986 Act her only option?

In 2024, the Supreme Court finally clarified the matter in Mohd. Abdul Samad vs The State of Telangana. A division bench of Justices B. V. Nagarathna and Augustine George Masih ruled that the 1986 Act does not take away a woman’s right to seek maintenance under the CrPC.

The court said the two laws coexist and that one does not cancel the other. A divorced Muslim woman, the top court held, can choose either path, or even both, to seek justice.

A Story That Refuses To Fade

Nearly four decades after Shah Bano’s plea for dignity, her story continues to echo. It has moved from the courtroom to cinema halls and from the constitution bench to the conscience of the nation.

‘Haq’ may be a film, but the real story began years ago in a small home in Indore. It still carries the same question that once echoed in the Supreme Court: what does justice truly mean for a woman who refuses to let go of her dignity?

Stay informed on all the latest news, real-time breaking news updates, and follow all the important headlines in india news andworld News on Zee News.

4 weeks ago

4 weeks ago