Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, just before the FY26 budget on Tuesday increased defence spending by 20%, questioned what the country's elites contribute to the national exchequer. It was a rare but telling admission from someone born into the elite, which includes the all-powerful army. However, in Pakistan, where the military, feudal, and business classes dominate both power and privilege, such rhetoric may ring hollow.

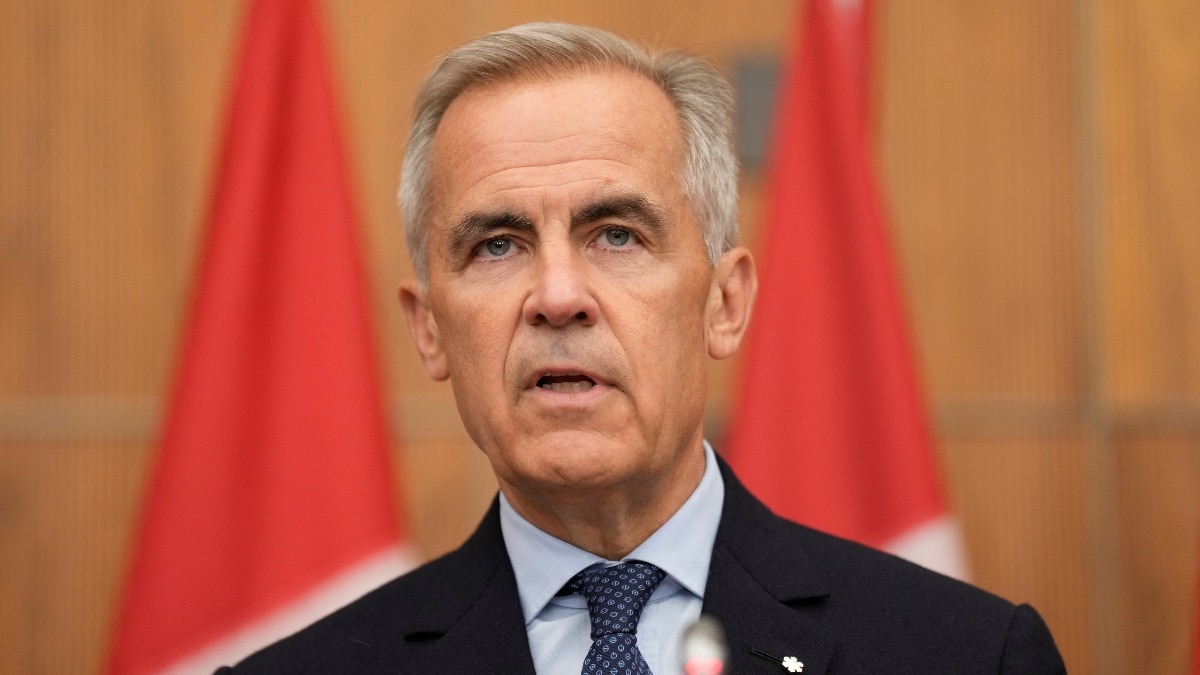

In Pakistan, the elite class, spanning political dynasties like the Sharifs and the powerful military leadership under top officers like Asim Munir, shape the country's policies, privileges, and priorities from the top down. (Image for representation: AFP)

Years after then-Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan said that the nation was a victim of "elite capture" in 2021, his successor and political rival, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, now appears to agree with that. Ahead of the presentation of Pakistan's annual budget on Tuesday, Prime Minister Sharif questioned the extent of the "elite's contribution" to the national exchequer.

As Pakistani economist Kaiser Bengali has long argued, the country's economic distress, political dysfunction, and social decay can be traced back to its entrenched elites. The real problem of the Islamic Republic is its privileged gentry, with the all-powerful, Army-led Establishment at the helm.

And it's this elite capture of Pakistan which has pushed the country onto the metaphorical ventilator where it's barely surviving on bailouts and donations.

Ironic, isn't it? Just before the budget, Sharif took aim at the elites, only for the same budget to hand a 20% hike to defence spending, presumably with a nod from the elite army brass. But then, Pakistan has been a nation of contradictions.

WHAT DID SHEHBAZ SHARIF SAY ABOUT PAK'S ELITES?

On Tuesday, ahead of the FY26 budget presentation, Shehbaz Sharif questioned the contributions made to the national exchequer by the country’s economic elite.

"The sacrifices the common man has made, the burden the salaried class has borne in the previous budget. They say 'we are salaried [class] but still gave Rs 400 billion to the treasury. What have the elite and the wealthy groups contributed compared to us?'," said Sharif, who belongs to a wealthy family of industrialists from Lahore.

"This is a question that the elite, including me, have to answer," he added.

Though Sharif's speech sounded optimistic on the surface, beneath it ran a clear undercurrent of frustration with a system where the privileged few evade fiscal responsibilities.

This has left the salaried and lower-income groups to shoulder the burden of economic reforms tied to the billions of dollars Islamabad is seeking from various institutions, including the IMF.

WHO ARE PAKISTANI ELITES, HOW PAKISTAN ARMY MILKS THE ELITE TAG

Pakistan's elite class is a complex nexus of wealthy industrialists, feudal landlords, politicians, senior bureaucrats, judiciary members, and, most significantly, the military establishment, which calls the shots there.

Pakistan's elite problem can be traced back to the failure to implement meaningful land reforms after Partition, which allowed feudal landlords to retain control over vast resources and political power. This entrenched dominance later merged with military and bureaucratic elites, creating a powerful nexus that continues to resist structural change and equitable economic policies.

Elites in Pakistan are the top 1% who control the country's wealth and earn an annual revenue of at least $100 million, a definition offered by political scientist Rosita Armytage in her 2020 book, Big Capital in an Unequal World: The Micropolitics of Wealth in Pakistan.

Moreover, in Pakistan, accurately assessing the income and assets of individuals and families is challenging, given that much of the economy is informal and wealth is often moved overseas, which is also facilitated by dual citizenship provisions there.

The Pakistan Army, which is a state within a state, holds unparalleled influence over the country's political, economic, and social spheres. The military's elite status is reinforced by its vast economic empire, which includes businesses, real estate, and stakes in industries ranging from cement to agriculture through entities like the Fauji Foundation and Army Welfare Trust.

The fascination with 'protocol' in Pakistan, (official courtesies, privileges, and security arrangements) is also part of the problem.

Pakistan's ruling elite, including politicians, civil and military bureaucracy, and their allies, benefit from subsidies and privileges worth approximately $17.4 billion annually, according to a 2021 UNDP report.

These include tax breaks, free housing, luxury vehicles, subsidised utilities, and prime land allotments. The military, in particular, enjoys significant perks, with senior officers receiving generous pensions, plots of land, and access to exclusive facilities.

The army's economic dominance distorts Pakistan's resource allocation, and prioritises defence over critical sectors like education and health, which have even received less than 1% of GDP combined.

HOW THE ELITE PROBLEM IMPACTS PAKISTAN

The Pakistani elite's disproportionate control over resources has exacerbated Pakistan's economic and social crises. The country's tax-to-GDP ratio, currently at 10.6%, is among the lowest in the region, with the government aiming for 14% to meet IMF loan targets.

The tax-to-GDP ratio measures how much tax a country collects compared to the size of its economy.

Wealthy elites, including feudal landlords and industrialists, often evade taxes through loopholes or political influence, leaving the salaried class and poor to shoulder the fiscal burden. For instance, agriculture, dominated by powerful landlords, remains largely untaxed, despite contributing significantly to GDP.

"The rich can still live luxurious lives in poorer countries, but the situation for the poor masses is becoming increasingly intolerable. Such is the situation in Pakistan today," political scientist and international development expert Syed Mohammad Ali wrote in an 2024 editorial piece in the Karachi-based The Express Tribune.

Ali argued that institutions such as the World Bank and IMF have facilitated elite capture in developing countries.

The elite problem has also perpetuated the economic dependency of Pakistan.

Sharif himself admitted earlier this month that Pakistan's allies, including China and Saudi Arabia, no longer expect Islamabad to approach them with a "begging bowl" but to engage in trade and innovation. Yet, Pakistan's reliance on bailouts and failure to curb elite privileges, such as the billions of dollars in annual subsidies for the richest 1%, hinders progress.

The same elites collectively own 9% of the country’s overall income, while the feudal land-owning class, which makes up just 1.1% of the population, owns 22% of all arable farmland.

Despite the dire economic indicators and repeated bailouts, Pakistan's ruling elite, civil, military, and corporate, remain unwilling to loosen their grip. Islamabad's refusal to confront elite dominance, particularly the military's unchecked economic and political power, lies at the heart of Pakistan's persistent crises and its failure to chart a sustainable future, underlined Salman Rafi Sheikh, a scholar from the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS).

Economist Kaiser Bengali, who was tasked with recommending structural reforms, and suggested abolishing 17 divisions and 50 departments, had to resign in a few months, after he saw the Sharif government going against the recommendations.

Shehbaz Sharif's critique of Pakistan's elites may not be rare, but is at least an acknowledgement of the systemic issue that has long undermined the country's stability. Pakistan's FY26 budget's prioritisation of defence spending over social welfare suggests that Sharif's admission may not be followed by meaningful action.

Published By:

Sushim Mukul

Published On:

Jun 12, 2025

Tune In

1 month ago

1 month ago