Last Updated:January 08, 2026, 10:06 IST

Maduro pleaded not guilty to sweeping US drug-trafficking and narco-terrorism charges, saying he was ‘kidnapped’ in a military raid and insisting he should be treated as a POW.

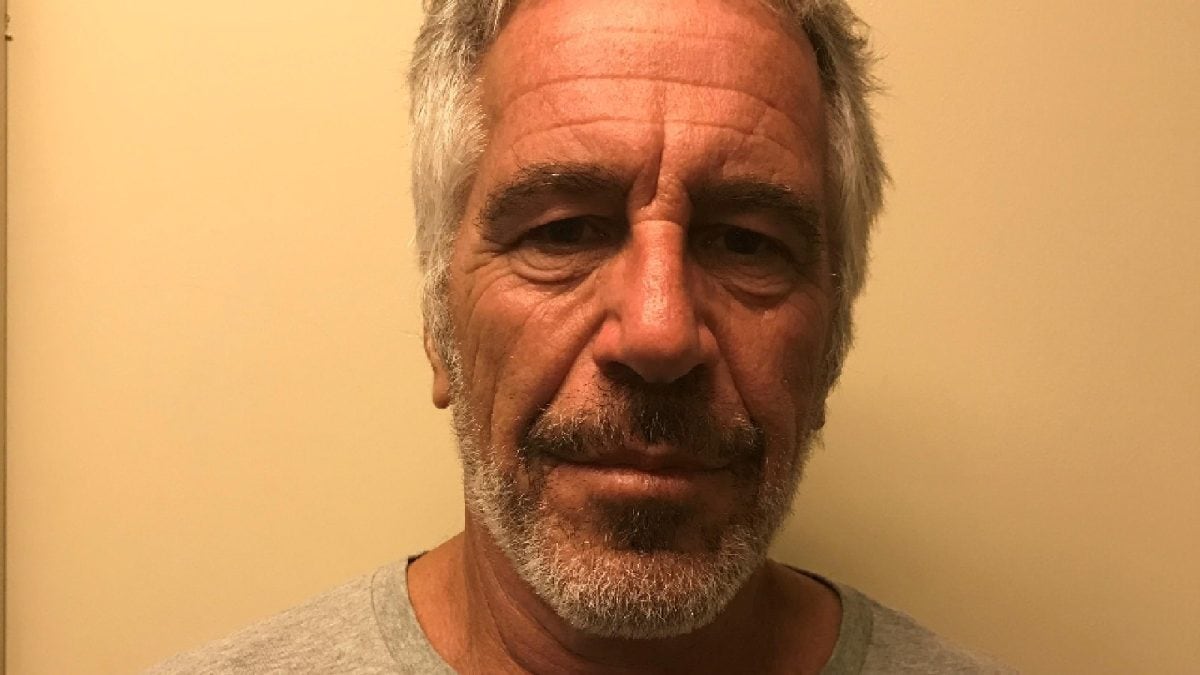

The sketch was released on Monday. (Image: Reuters)

The dramatic capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by US forces has shifted into its legal phase. On Monday, the ousted leader appeared before a federal judge in New York and pleaded not guilty to sweeping charges of narco-terrorism, cocaine trafficking and conspiracy.

His first court appearance showed that the legal battle ahead will be about far more than drug indictments. It raises deeper questions about how the United States justifies the operation, what legal protections Maduro can claim, and whether his transfer from Caracas to New York can be treated as a conventional criminal prosecution.

Barely 48 hours after US Delta Force personnel seized Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, from a compound in the Venezuelan capital, the leader stood before Judge Alvin K Hellerstein and said he had been “kidnapped". Speaking in Spanish, he declared, “I am a decent man, the president of my country," insisted he was “not a criminal defendant at all", and described himself as a “prisoner of war".

His statement immediately raised questions about the legal character of the US operation, the status he seeks under international law and the challenges that could complicate the trial.

The charges themselves are sweeping, alleging that for more than two decades, Maduro and his inner circle turned Venezuela into a major transit hub for cocaine bound for the United States.

What Exactly Are The US Charges Against Maduro And His Family?

According to the 25-page indictment, the alleged conspiracy dates back to 1999, when Maduro was first elected to public office. Prosecutors accused him, his wife Cilia Flores, his son Nicolás Ernesto Maduro Guerra and senior Venezuelan allies of running what they described as a “relentless campaign of cocaine trafficking".

The indictment said this network partnered with powerful cartels and armed groups, including Colombia’s FARC, Mexico’s Sinaloa and Zetas cartels, and the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua, all of which the United States designated as terrorist organisations.

Prosecutors alleged that Maduro, Flores, Maduro Guerra and their allied officials provided law-enforcement cover and logistical support for moving cocaine through Venezuela, knowing the shipments would ultimately be transported north towards the United States. According to the indictment, this group used state institutions to facilitate trafficking routes, shield drug operations and profit from the proceeds.

One section of the indictment claimed that between 2006 and 2008, when Maduro served as foreign affairs minister, he sold diplomatic passports to individuals he allegedly knew were drug traffickers. This, prosecutors say, allowed money from Mexico to be moved back to Venezuela “under diplomatic cover". Flores, who led Venezuela’s Assembly, is alleged to have accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars in kickbacks linked to safe drug shipments. Their son is accused of regularly flying to Margarita Island with packages believed to contain drugs.

The indictment also named Hector Rusthenford Guerrero Flores, known as “Niño Guerrero", who is described as a leader of the Tren de Aragua gang. While US President Donald Trump has publicly accused Tren de Aragua of carrying out violence inside the US and of having ties to Maduro, the indictment itself does not detail a specific link between Maduro and Guerrero.

In court, Maduro’s lawyers argued that he is immune from prosecution because he remains the head of a sovereign state. He dismissed all allegations as politically motivated and reiterated that his transfer to the United States was illegal.

Why Did Maduro Call Himself A ‘Prisoner Of War’?

Maduro’s insistence that he is a prisoner of war is not a rhetorical flourish but a direct challenge to the legal basis of his capture. By framing the operation as military rather than civilian, he is signalling that the US action should be interpreted as part of an armed conflict, not a criminal investigation.

In his telling, he was not arrested by law enforcement but seized in a military raid, and therefore cannot be treated as an ordinary defendant.

The Geneva Conventions govern the treatment of prisoners of war. A prisoner of war is not prosecuted simply for being part of a hostile force, is not tried in civilian courts for wartime conduct and does not face accusations of personal criminal guilt. Their confinement cannot be in close quarters unless necessary for safety, and they are generally released at the end of a conflict rather than sentenced by a judge.

Maduro appears to be invoking this framework to argue that he cannot be subjected to a US federal criminal trial. The New York Times noted that if he were considered a prisoner of war, his treatment would fall entirely under international humanitarian law. The classification would upend the prosecution because a prisoner of war is not processed through civilian courts and is not held on criminal charges.

However, Judge Hellerstein made it clear during the arraignment that the case will move forward like any other federal prosecution. When Maduro began repeating that he had been “kidnapped" and was an “innocent man", the judge cut him off, saying there would be “a time and place" to raise such arguments.

Why Is The POW Claim Unlikely To Succeed In Court?

According to legal experts, Maduro’s strategy may create delays but is unlikely to prevent the case from being treated as a criminal matter.

Daniel C Richman, a Columbia Law School professor and former federal prosecutor, told The New York Times, “Even if he raises claims of immunity or international law, this will be decided as a criminal case".

In a separate remark, he added, “In a criminal case, there is a basic expectation that a defendant will, at least initially, accept the court’s authority and behave accordingly. When someone outright rejects that jurisdiction, it can significantly disrupt and complicate the proceedings."

The prosecution, meanwhile, has described the Caracas raid as a law-enforcement operation aimed at bringing a long-indicted suspect before a US court, citing the 1989 capture of Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega as precedent. In that case too, a foreign head of state forcibly transferred to the United States was ultimately tried on drug charges in a civilian court.

Maduro’s reference to the laws of war also sits uneasily alongside the broader language the administration has used elsewhere. For months, the US has spoken of maritime actions against drug-linked vessels in quasi-military terms, and some operations have been justified through a classified Justice Department memo arguing that the United States is in an armed conflict with certain drug cartels.

Maduro is now attempting to use this ambiguity to argue that the US is contradicting itself: describing its actions as military when convenient but insisting on civilian jurisdiction when prosecuting him.

Yet none of this affects the fact that US courts have accepted a criminal indictment against him. Judge Alvin K Hellerstein has not entertained the prisoner-of-war claim, and for now, the Department of Justice maintains that Maduro is simply another defendant facing serious federal charges.

What Happens Next In The Legal Process?

The case is expected to be long and complex. Much of the evidence is rooted in intelligence assessments, witness testimonies and classified material. This alone could delay proceedings for years. Maduro’s refusal to recognise the court’s jurisdiction adds another procedural obstacle, introducing the possibility of hearings on immunity and the legality of his transfer.

However, legal scholars say that even if Maduro raises international-law claims or asserts immunity as a head of state, these arguments will most likely be rejected. The criminal charges remain in force, the judge has asserted jurisdiction and the prosecution intends to proceed.

What remains clear is that Maduro’s strategy is aimed not only at the courtroom but also at the international political arena. His claim of being a prisoner of war is designed to influence global perception, rally allies, cast doubt on the legality of the US raid and frame himself as a victim of external aggression rather than a criminal defendant.

For now, the court in New York will continue treating him as precisely that: a defendant facing grave criminal charges, not a prisoner of war. His arraignment marks the beginning of what is likely to be one of the most legally and politically contentious trials involving a foreign leader in recent decades.

First Published:

January 08, 2026, 09:54 IST

News explainers The Sweeping US Case Against Maduro And Why He Called Himself A 'Prisoner Of War' In Court

Disclaimer: Comments reflect users’ views, not News18’s. Please keep discussions respectful and constructive. Abusive, defamatory, or illegal comments will be removed. News18 may disable any comment at its discretion. By posting, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Read More

4 weeks ago

4 weeks ago