Good morning. A few weeks ago, 18-year-old Tamsin Jarman-Smith, born and raised in a small town just outside Blackpool, sat on a battered sofa at House of Wingz, a community youth organisation tucked down an alleyway a few streets from the beach, and explained what it felt like to be a young person growing up in a coastal town.

“I’m lucky because I found this passion for dancing and I come to this place, which has saved me I think, especially my creativity and hope for opportunities for myself, but lots of people my age feel like there is nothing here for them,” she said.

“Everyone just tells you that your town is crap and that the only good things about it is the tourist attractions but they’re not even for the locals. There aren’t many good jobs, the housing is bad, not many people can afford to leave. Lots of people just feel trapped.”

Research shows there are good reasons for them to feel this way.

Young people in seaside towns in England and Wales are markedly more likely to face deprivation, poor housing, lower educational attainment and fewer employment opportunities – and, in England, are almost three times as likely to struggle with an undiagnosed mental health illness as their peers inland.

This week the Guardian launched Against the Tide, a year-long reporting project aiming to explore why teenagers and young people in coastal towns and communities across the UK are so disproportionately worse off in so many areas of their lives.

For today’s newsletter I talked to Avril Keating, professor of youth studies at UCL’s Institute of Education, about the issues affecting young people in our coastal towns and what needs to change.

Five big stories

Europe | Talks over a British and French migration deal remained deadlocked on Wednesday night, as negotiators haggled over how much Britain will pay towards the cost of policing small boat crossings.

UK news | Campaigners have decried as “dangerously naive” the UK government’s sweeping deal with Google to provide free technology to the public sector.

Europe | Police have raided the headquarters of France’s far-right Rally and seized documents as part of an investigation into alleged illegal campaign financing.

UK news | Thames Water has refused to claw back almost £2.5m paid to senior managers from an emergency loan that was meant to keep the failing utilities company afloat.

Housing | The Bank of England has rolled out looser mortgage rules that policymakers hope will help 36,000 more first-time buyers on to the housing ladder each year.

In depth: ‘You feel like you’ve been forgotten’

In recent years the fate of coastal towns has emerged as one of Britain’s most pressing social issues, one that successive governments have recognised but failed to address.

Formerly thriving towns now consistently dominate UK government deprivation statistics. Some researchers we talked to described a “salt belt” of deprivation that speaks to a broader lack of resources and social and public infrastructure – conditions that corrode and limit opportunities and aspirations.

According to UCL’s Avril Keating, young people in these communities – meaning 15- to 25-year-olds – are some of the most affected.

“These are young people who are trying to figure out how to become independent adults in places that tend to have very limited opportunities,” she said. “They often feel that these towns have nothing to offer them and they have been left behind – and in many ways they are right.”

What are some of the biggest challenges for young people in coastal towns?

When asked why she thought young people in seaside towns were so markedly worse off than their peers inland, Keating said there was a combination of issues at play: crumbling public services; insufficient local transport infrastructure further isolating young people in “end-of-the-line” towns; seasonal coastal economies providing temporary employment in the summer months but then nothing for the rest of the year; and generational unemployment and household poverty.

One youth policymaker in St Ives told Keating’s researchers that the seasonal job opportunities for young people are “like a glass ceiling – but it’s made of ice-cream and chips and pastries. For many young people it’s limiting.”

The lack of opportunities coupled with the physical decline of their towns and the stigma of being associated with deprived communities – feeling like, as one young person in Blackpool described, “just this poor person living in a shithole” – leads many to believe that their only option is to leave.

“These are places where local people often feel a strong connection to their town, but what was surprising to see from our research was that so many young people felt that they had to move away to make something of themselves,” said Keating.

The “brain drain” of young people from coastal communities not only leaches these towns of future entrepreneurs, business owners and skilled workers, but leaves the dilemma of “what happens to those who want to leave, but can’t”, said Keating. “It can create a feeling of being trapped, a sense of hopelessness, and this can lower pride and aspiration.”

Research has shown that young people in the most deprived coastal areas are suffering from worse mental health problems than those inland, have higher levels of self-harm and are more likely to die from drug poisoning.

What do young people themselves say they need?

Over the past few months, Guardian reporters (including myself) have begun to travel to coastal towns to talk to young people about their lives. Older teenagers in Southend-on-Sea talked about how hard it was to live in a town where the seafront was busy with tourists enjoying the beach, while shops on the high street were boarded up and all the youth clubs were closed. “There is nothing here for us. The only good stuff is for the tourists. It’s just not a place I’d want to raise a family,” said one.

Cohen, an 18-year-old in Grimsby, said he was happy living there but was struggling to find a way of building a life for himself. “It’s not easy to get jobs here,” he said. “I’ve been looking for the past few months but I keep getting turned down. I recently applied for a job at a local holiday park, but was told it had already been filled.”

Yet we also met many young people who had found good reasons to stay, often through finding local community groups that allowed them to build their confidence and aspirations.

Lisa February, a 25-year-old from Grimsby, decided to stay when she found a local theatre group helping aspiring young artists across north-east Lincolnshire. “I don’t see a version of my life living somewhere else,” she said. “I feel a responsibility to the place that has given me all these opportunities.”

What needs to change?

Keating said it was clear from her research that young people in English coastal towns – whether they are in tourist resorts or former fishing or shipbuilding communities – had “almost universally been marginalised and ignored in both local and national debates and policies about the factors that shape their own lives”.

She said investment and public money was almost always directed to other groups – such as older people or young children – and that the shuttering of youth services and support programmes was a “real scandal, considering the enormous challenges facing young people and the deprivation that many of them are facing”.

Keating said young people overwhelmingly needed to see that their lives were valued and be given something to do and a place to go. This meant urgent investment in youth services and subsidised travel, better education opportunities (her team’s recent report cites Camborne as an example of where a new university has supported the retention of young people in the area) and – crucially – listening to young people about the future of their towns.

“We need stop ignoring them”,” she said. “It’s a cliche to talk about young people as the future but if you’re not investing in young lives in coastal communities you’re shoring up bigger problems down the line. How can you expect anything to change for them or their communities?”

skip past newsletter promotionafter newsletter promotion

Read more in the year-long series Against the tide here.

What else we’ve been reading

I was gripped by this interview by Anita Chaudhuri with Joanne Briggs about her father’s extraordinary journey (pictured with her above) from being a well-known scientist to a liar and fantasist. Aamna

Diplomatic editor Patrick Wintour asks if the bromance between Trump and Putin is over and what this could mean for Ukraine – and the rest of the world. Annie

For 100 years the Welsh have been Labour’s most loyal voters, but, as Bethan McKernan explores, could Plaid Cymru and Reform finally be breaking their grip? Aamna

This is a chilling but important read from Judith Levine looking at the potential transformation of Ice into the largest domestic police force in the US. Annie

Britain is still far from being a totalitarian state, Owen Jones argues, but the arrest of an 83-year-old retired vicar for holding a placard in support of Palestine Action signals a troubling drift towards authoritarianism. Aamna

Sport

Football | It was England 4-0 Netherlands in the women’s Euro as Lauren James starred and Jess Carter’s move to centre-back worked perfectly. Jess Fishlock scored Wales’s first goal at a major tournament but the European debutants were beaten 4-1 by France in Group D.

Tennis | Iga Świątek held her nerve to reach the Wimbledon semi-finals for the first time, holding off a bold fightback from Liudmila Samsonova to claim a 6-2, 7-5 victory. Belinda Bencic will face Swiatek in what is also her first Wimbledon semi-final after holding her nerve to beat the 18-year-old sensation Mirra Andreeva 7-6, 7-6. Novak Djokovic was given a fright by the lively young Italian Flavio Cobolli before coming through 6-7 (8), 6-2, 7-5, 6-4; while Jannik Sinner beat Ben Shelton 7-6 (2), 6-4, 6-4 to reach his fourth grand slam semi-final in a row.

Formula One: Christian Horner has been dismissed as Red Bull’s team principal. Horner, who has led the team since its inception in 2005, will be replaced by Laurent Mekies, the principal of sister team Racing Bulls.

The front pages

“Anglo-French migration deal hangs in the balance” says the Guardian print edition while the Times predicts a result with “50 migrants a week will be sent to France”. Top of the bulletin in the Financial Times is “US tech boom propels AI chipmaker Nvidia to become first $4tn company”. “Geri’s F1 husband shunted out” says the Metro because Ginger Spice is more interesting than Christian Horner. “Benefits pay more than being in work” – that’s actually a comparison between the minimum wage (not the average wage) and “full handouts” (unemployment and sickness benefits) in the Telegraph, so “Benefits CAN pay …” would seem more accurate. But that doesn’t stop the Daily Mail: “Proof work DOESN’T pay under Labour”. The i paper has “Labour will target rich but won’t call it a wealth tax, says minister”. The Express vents “Fury at junior doctors’ strike”. The Mirror features the “Astonishing bravery of Southport children” as retold at the public inquiry into the stabbings.

Today in Focus

Is it time for a wealth tax on the super-rich?

After changes to the welfare reform bill failed to save money, the millionaire Dale Vince thinks it’s time for people like him to contribute more to the public finances. Arun Advani considers how a wealth tax could work and if it’s time for Labour to introduce one.

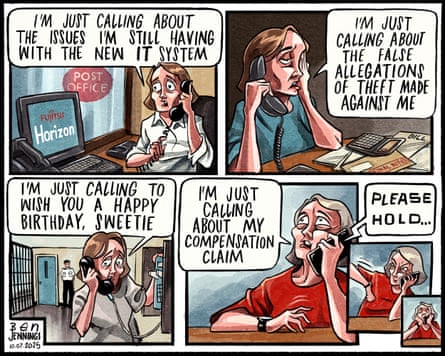

Cartoon of the day | Ben Jennings

The Upside

A bit of good news to remind you that the world’s not all bad

The Bayeux tapestry will return to the UK for the first time in more than 900 years, as part of a landmark loan agreement between Keir Starmer and Emmanuel Macron.

The tapestry, which comprises 58 scenes, is widely believed to have been created in England during the 11th century, and was likely commissioned by Bishop Odo of Bayeux.

This 70-metre embroidered cloth vividly depicts the 1066 Norman invasion and the Battle of Hastings, in which William the Conqueror claimed the English throne from Harold Godwinson, becoming the first Norman king of England.

The tapestry will be displayed at the British Museum starting in September next year, in exchange for key Anglo-Saxon artefacts, including the treasures from the Sutton Hoo ship burial, the Lewis chessmen and other invaluable relics.

Sign up here for a weekly roundup of The Upside, sent to you every Sunday

Bored at work?

And finally, the Guardian’s puzzles are here to keep you entertained throughout the day. Until tomorrow.

1 month ago

1 month ago