In the run-up to the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, journalists covering the preparations for war became familiar with the concept of “stovepiping”.

The term described the tactic of pushing intelligence to key political decision makers, bypassing checks and balances within the system.

A more familiar word would be cherrypicking: in the case of the Iraq war, the administration of George W Bush believed that Saddam Hussein was building weapons of mass destruction, and – minded to act on that belief – sought proof of its proposition. Convinced that it was right, it sought to streamline information that confirmed its bias. What fell by the wayside were conflicting views.

Because intelligence is ultimately about assessing the likelihood of things which are difficult to know, stovepiping means a finger is put on the scale – and that process of assessment becomes flawed.

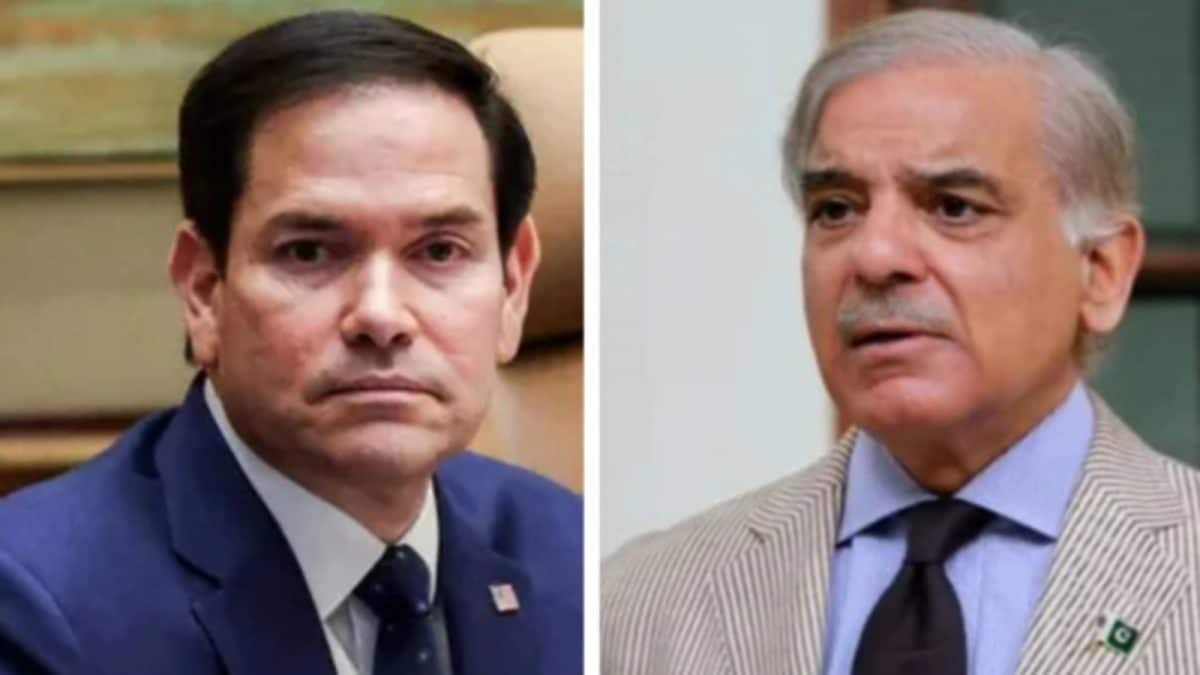

If all this sounds uncannily familiar, it is because Donald Trump and some of his most senior officials – including the secretary of state, Marco Rubio, Vice-President JD Vance, the CIA director, John Ratcliffe, and defence secretary, Pete Hegseth – appear to be stovepiping in the crudest way.

While the Bush administration, supported by the government of Tony Blair in Britain, turned the intelligence justification for war into a slippery PR exercise that entangled senior intelligence and military officials, Trump has applied the same approach he does to everything.

Now, his sweeping statements over the damage done to Iran’s nuclear facilities have turned into an inevitable test of loyalty for his officials who have scrambled to toe the line, even as intelligence leaks have raised doubts over the veracity of his claims.

After the US airstrikes on Isfahan, Natanz and Fordo, Trump said on Saturday that “Iran’s key nuclear enrichment facilities have been completely and totally obliterated”. But on Tuesday a leaked assessment by the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) concluded that the attacks probably only set back the nuclear program by a few months – and that much of Iran’s stockpile of highly enriched uranium (HEU) may have been moved before the strikes.

His ego piqued, Trump and those around him have made ever more outlandish claims: the attack was historically equivalent to the Nagasaki and Hiroshima bombs; the operation was the most sophisticated in human history.

The Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) also said Iran’s stockpile of HEU could not be accounted for. But Trump denied that the HEU had been moved, posting on social media: “Nothing was taken out of facility.” On Friday, Hegseth followed suit, saying he was unaware of intelligence suggesting the material had been moved.

The world has become used to Trump’s tantrums, but the trustworthiness of the intelligence – before and after the attack – is profoundly important because it speaks to the credibility of the US on the most important issues of international security.

Indicative, and more important than Trump’s outbursts over the level of damage, has been the way in which the intelligence justifying the attack has been reshaped.

skip past newsletter promotionafter newsletter promotion

In testimony to Congress earlier this year, Tulsi Gabbard, Trump’s director of national intelligence, reflected the intelligence community’s official view.

She conceded that Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium was of a size “unprecedented for a state without nuclear weapons”, but the spy agencies’ assessment was that Iran had not recommenced work on building a nuclear weapon since that effort was suspended in 2003.

Bullied by Trump, who last week dismissed her assessment, Gabbard quickly fell into line, claiming her remarks had been taken out of context by “dishonest media” and that Iran could have been on the brink of making a weapon within “weeks or months”.

Trump’s attack on Iran, as a Rolling Stone headline memorably put it last week, was based on “vibes not intel”.

Pressed by NBC why the Trump administration had chosen to ignore the intelligence estimate, Vance appeared to confirm this, saying: “Of course we trust our intelligence community, but we also trust our instincts.”

While the vice-president framed it as a collective stance, the reality is that Trump has long distrusted the US intelligence community – a friction that dates back to his first term, when he pushed back at claims that Russian hackers had interfered to help him get elected, and appeared willing to believe Vladimir Putin’s word over his own spy agencies.

In that same period, Trump dismissed intelligence assessments and pulled the US out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the 2015 nuclear deal signed between Iran and other countries. He also appeared to prefer his own “vibes” over intelligence assessments of North Korea’s eagerness for detente.

It is that history of trusting his own feelings above the US intelligence community that appears to add weight to the suspicion Trump was personally swayed by Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, whose claims on Iran’s nuclear weapons he has often parroted.

Trump’s intervention on the issue of the damage done to Iran’s nuclear facilities is also crucially important. By setting out the narrative that the spy agencies are loyally expected to adhere to, Trump is slamming shut a door on actual investigation and intelligence-gathering.

Proper curiosity and scepticism, Trump and those around him have made clear, will not be rewarded but could be damaging to careers.

In the postmortem of the Iraq war, much attention was focused on the shutting down of debate within US and UK intelligence agencies – not least the lack of a culture of oppositional “red team” analysis designed to challenge orthodox assumptions.

As the US president attempts to bend intelligence to his instincts, the problem now is not that there is no “red team”, but that the entire intelligence community is now expected to be Team Trump.

4 hours ago

4 hours ago